For a simple life, people usually say that a lunar month lasts 28 days. This reflects the fact that there are different criteria for deciding when an orbit starts and ends (relative to the earth’s surface or relative to the position of the sun). But there are two different figures for the duration of a lunar month: about 27.32 days or about 29.53 days. It orbits the Earth in what’s known as one lunar month. On top of all this, there’s the Moon-clearly visible from Earth.Therefore, developers who use these two systems are at least spared that complexity. The calendar implementation that PostgreSQL uses, and that YSQL therefore inherits, does honor the ordinary rule for when leap years occur. There’s a rule for when one minute occasionally becomes 61 seconds. There’s also the phenomenon of leap seconds to accommodate the fact that the length quoted by Wikipedia, 365.2425 days, is an approximation.So 2000 was a leap year, but 1900 wasn’t and 2100 won’t be. Humans have adopted a convention to accommodate this: a standard year lasts 365 days and a leap year lasts 366 days leap years usually come when the year number is divisible by four (2012, 2016, 2020, and so on) but when it’s a century year (1900, 2000, 2100, and so on) it will not be a leap year unless it’s divisible by 400. It says that the average length of one year, over a 400 year sample, is about 365.2425 days (to four digits of decimal precision). There is no astronomical reason for the ratio of these two durations, one year to one day, to be an integer-and it isn’t.And we call the duration from when a spot on planet Earth experiences its longest day until it next experiences this one year. We call the duration from when a spot on planet Earth sees the sun at its zenith until it next sees it there one day. And, distinct from this, we experience the cycle of changing length of daylight and changing weather-in other words seasons. As a result, we see the sun rise and set-in other words, we experience day and night. And its axis of rotation isn’t normal to the plane of its solar orbit. Humans have evolved, and developed language and thought, on planet Earth-which both rotates on its own axis and orbits the sun.The conceptual difficulties stem from these phenomena: This explains my choice of this post’s title. And it’s my aim here to provide you with a powerful headache analgesic. I really think that I’ve found a way to constrain the complexity and the paradoxes. Looking for logic in dates/times/calendars is a recipe for a continuous pounding headache. I asked endless questions on the pgsql-general email list and received enormous help from that source. I struggled with all this while I was doing the required study to prepare for my documentation task. But it turns out that the rules here are complex and confusing. This sounds as if it couldn’t be simpler. And when you add (or subtract) an interval value to (or from) a timestamp value, you get a timestamp value.

When you subtract one timestamp value from another, you get an interval value. This second part deals with durations (how long things last).

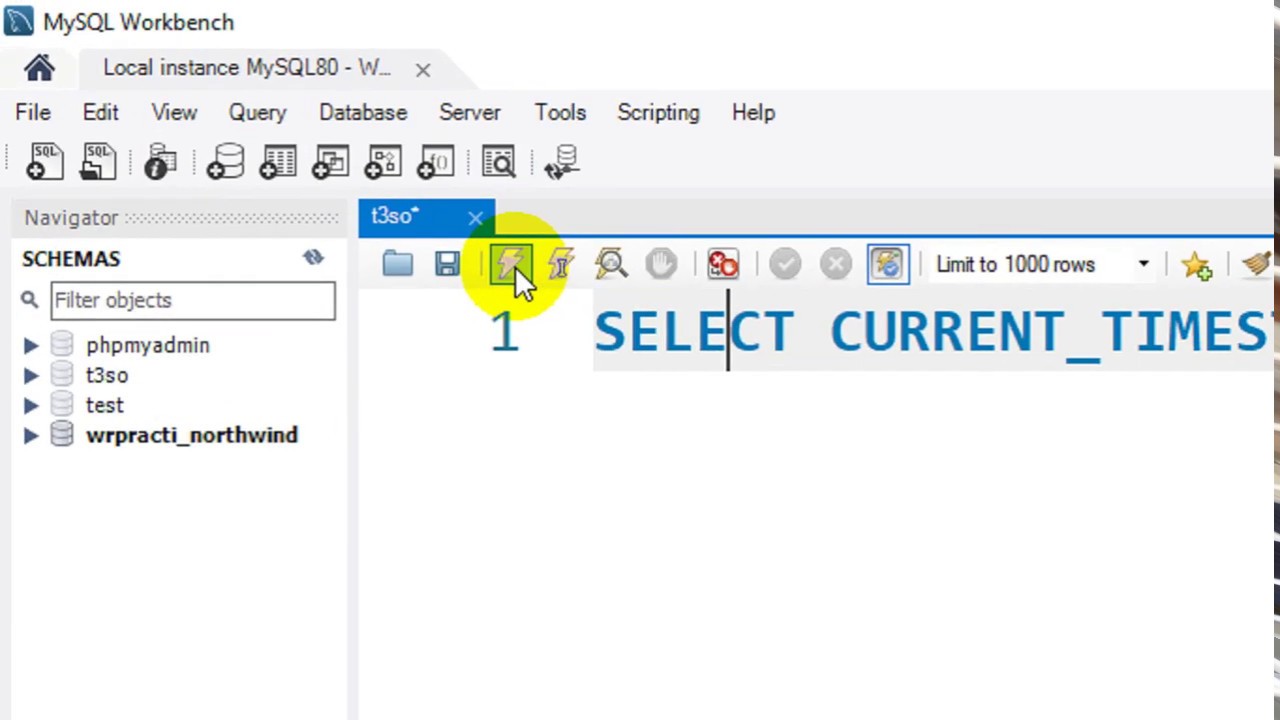

#POSTGRES CURRENT TIMESTAMP MINUS MINUTES CODE#

I’ll also assume that you downloaded and installed the companion code kit for the YSQL date-time documentation. I’ll assume, here in the second part, that you’ve read the first part. I’ll use, hereinafter, the short spellings (plain) timestamp and timestamptz, respectively, for these-and timestamp to denote either one of these. The relevant data types here are time, date, and timestamp-where the latter has a without time zone and a with time zone variant. The first part dealt with the basic business of representing moments (when things happen).

#POSTGRES CURRENT TIMESTAMP MINUS MINUTES SERIES#

This is the second of a two part blog post series about the date-time data types that PostgreSQL, and therefore YSQL, support.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)